When the University of Lethbridge was launched in 1967, old academic formulas for success, adopted from other places or times, were less the mindset of the day than dreams and imaginings for a different kind of university. New ideas merged with real experience while unexpected opportunities and challenges modified almost every plan along the way.

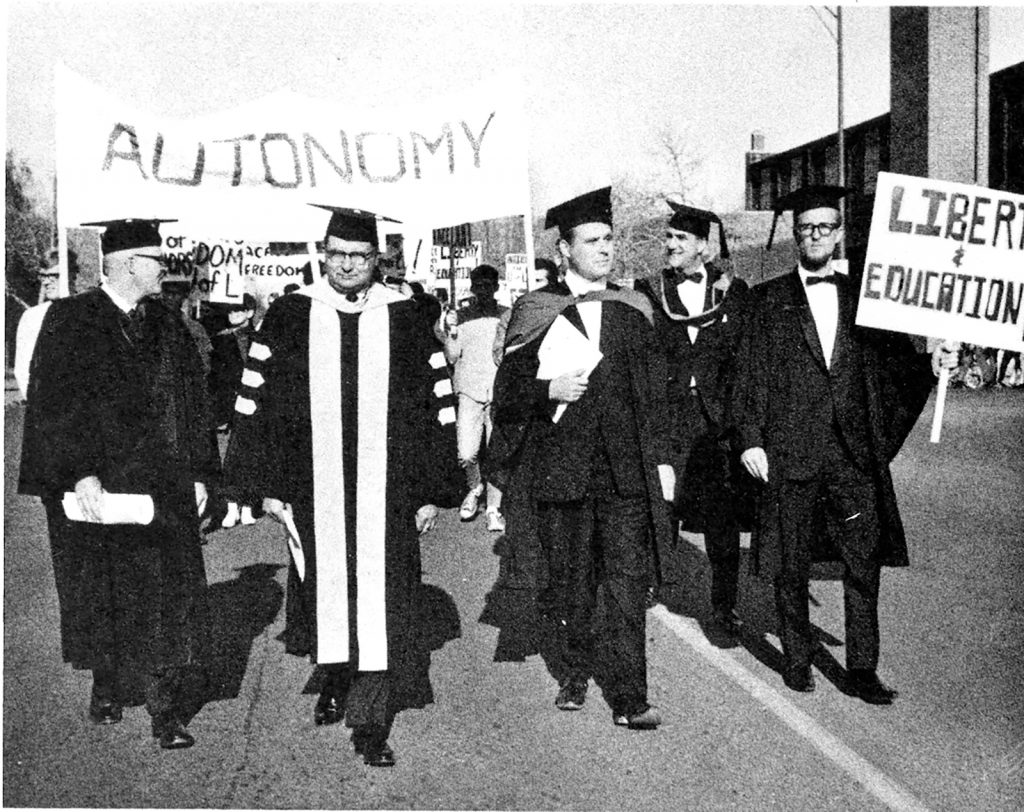

Following the U of L’s first convocation in May 1968, faculty, students and community members marched down Third Avenue to Galt Gardens in support of the U of L’s autonomy in the decision to locate campus on the west side. Leading the march (second from left), Dr. Russell Leskiw (LLD ’93), the first acting president.

The persistence of special individuals, a fortunate civic environment, a brief political opportunity and lucky timing were the chief elements at the outset. Although Lethbridge was already home to a junior college, the city and the region appeared to offer a population base too small to support a public university in addition. Yet, in the 1960s, many civic leaders were interested in furthering an economically steady and culturally rich education industry to replace the old image of Lethbridge as a coal town. Persistence came specifically from a few very determined persons — such as Kate Andrews and Dr. Van Cristou (LLD ’84) to name but two — who were unrelenting advocates for a university. They were accompanied by a chorus of others, including the mayor, the city council, the Chamber of Commerce, the Lethbridge Herald and several academics already teaching at the College (then Lethbridge Junior College). Political support came from the province’s Social Credit government (soon to be swept aside by Peter Lougheed’s Conservatives) which, despite lacking intimate personal knowledge about post-secondary education, possessed a collective faith in the benefits of higher education, and wished to reward faithful voters in southern Alberta. A modest

regional prosperity coupled with the social enthusiasms of the 1960s furthered greatly

the quest for a university.

The first few years were inauspicious. The University needed an early visual presence but had none. The University shared facilities with the College, each institution swapping the use of classrooms, a library and other physical spaces and juggling schedules to make certain it all worked. This logistical miracle was softened in a minor way through the purchase of some portable trailers to house University academic offices and service buildings (a few of these remained in service until recently). Through these early years, however, the physical presence of the U of L was underwhelming at best.

From the beginning, many argued that the University could not live in the shadow of the College or be seen as an extension of the College. Autonomy for the University did not just depend on legal determinations, they believed, but was a matter of location and visibility. The community was split. Some, especially land developers, favoured the use of ample land available south of the city and near the College. To the shock of most, the University itself proposed moving to the west side of the Oldman River, where only a few farms and ranches but no urban community existed. Support came from the City and the Herald, but local MLAs and the provincial government were wary. Tensions ran high. Members of the University community — administration, faculty and students in particular — convinced themselves that everything was at stake in winning the battle for autonomy on the west side. At the height of the fervour, a dramatic march for “autonomy” was held in downtown Lethbridge. The victory in acquiring the right to build on the west side marked the first clear example of a U of L legacy for stubborn independence.

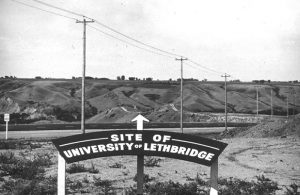

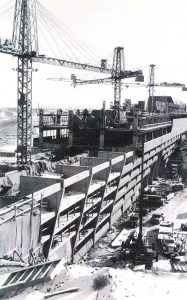

The west side provided a blank canvas. The University and province hired Dr. Arthur Erickson (LLD ’81), one of Canada’s most renowned architects, as the campus planner for five years. Meanwhile, George Watson, a local architect who had considerable skill and insight, was tasked with providing a Physical Education building at the top of the coulees, a site so well executed that its original bones remain part of the vast physical education complex in existence today. Erickson’s ambitious plans were based on placing a long university building well down into and across the coulees, one that could be joined later to other buildings stretching north and south across the coulees. At first, that positioning surprised and concerned many in the university and community. Rumours and urban legend had it that the University would slide into the river, and every so often a few of these “I-told-you-so’ers” raised their prophetic voices, proclaiming an inevitability that never happened.

By moving to the west side, the University gained autonomy but sentenced itself to several years of isolated existence. One small paved road led south from Highway #3 and 3A to a parking lot near the Physical Education building. From there, everyone who commuted — meaning most people who worked and studied there minus a small number of students in residence — walked down a long windswept sidewalk to University Hall. Although the walkway was later covered with a white plastic canvas to protect against the elements, the walk to Erickson’s magnificent building was cold in the winter, hot in the summer, and generally depressing. The walkway symbolized the lonely separation of the University from the inhabited world. Students who resided in the low-ceilinged floors below the fifth floor sometimes found their existence remote and despairing. Others, generally away from home for the first time, established a kind of frontier camaraderie living in close quarters with other students, where even contact with the city and its shops

meant a vigorous expedition.

Faculty and staff were never in full agreement about University Hall (then the Academic and Residence building). Recent interviews of those who worked and studied there suggest that more than half did not like the long, stark, white hallways and found the building depressing. Others reveled in the building’s unique architecture and its powerful visual statement. Forgotten by many was the fact that the building was relatively inexpensive to build, fitting into the

$17.5 million the government funded to build the campus.

Autonomy was not just an issue of local concern. Founders of the U of L were aware that the University of Alberta might conspire to make the U of L a mere branch or subordinate unit of the U of A. And, over the years, some supporters of the University of Calgary even suggested that the U of L should, for economy’s sake, be packed up, its resources and students shifted north to Calgary.

Dr. Sam Smith (LLD ’90), the U of L’s first official president speaks to the crowd at the sod-turning ceremony in 1969.

The dramatic physical foothold represented by University Hall, first occupied in 1971, was more than matched by its early administrative leaders. Dr. Sam Smith (LLD ’90) was brought to Lethbridge from Edmonton, and it soon became clear that Smith — gregarious, charming, quick witted and humorous — was the perfect personality for the new school and for the community. Smith represented the confidence the rest of the University community either had, or wished it had, and won over city leaders, members of the Board of Governors, and faculty, staff and students alike. Leadership, in Smith’s eyes and in the eyes of many of the University’s early members, meant furthering the democratic institution that many of the school’s most ardent supporters and faculty had long sought.

While Smith gave a positive, almost brash, public face to the University, his vice-president, Dr. William Beckel (LLD ’95) complemented Smith’s strengths with different talents. In the early 1960s, Beckel had been the builder, in the most complete sense of the term, of Scarborough College, a stand-alone liberal education college that was an independent part of the University of Toronto. Beckel knew budgets and buildings, and large-scale planning. Although he frightened some faculty in late 1971 (with what came to be known colloquially as his “Dear Colleague” letter) by suggesting that a bad Alberta economy might lead to some staff cuts, he was always dedicated yet cautious. It was this quality that allowed him to present the logic of the programs and plans of the University’s academic community, in a convincing and confident way, to a Board of Governors that might otherwise have wanted to dabble more directly in exclusively academic matters.

Construction of University Hall, which was then referred to as the academic and residence building.

Caught up in the total newness of the U of L, and construction of a university on the fly, were the people for whom these efforts were being made — the student body. Although they came to the U of L for various reasons, many simply considered the University of Calgary or the University of Alberta too remote. Calgary and Edmonton were large cities and, many reckoned, the monetary cost would be hard for them to absorb. Most were first-generation university students, which meant that they arrived uninformed about what a university was or could be, but also untainted by their parents’ or relatives’ prejudices about what a university should be. Some were timid, but even the most confident were charmingly deferential. Most did not expect the high visibility they would have in a small university setting.

At first, lack of anonymity intimidated some early students. The perceived upside to being pioneers in a new educational institution was soon impressed on most, however. Because class sizes were generally small, individual students were conspicuous to their professors. Attentiveness and intellectual engagement, even in lecture classes, was more intense when only a dozen other students occupied the room. If the proper idea of a university is a place where students are known one by one, and their needs addressed individually, the U of L was a true university from the outset.

Other factors also caused professors and students to elevate their academic expectations of themselves and others. The promise of a new era in education, one more student-oriented, was part of the equation. The opportunity for individual students to recognize and pursue their specific interests and strengths was another. Without the distraction of graduate students, faculty generally lavished their attention on promising undergraduates. Many students became research assistants to their professors. In such an atmosphere, many students were emboldened to pursue special intellectual interests through independent studies courses, or the innovative Colloquium Studies program. Because the U of L was one of the first schools to accept senior students readily — persons who were returning as mature adults after engagement in the so-called “real world” — at least some element of diversity enhanced the classroom experience as well.

Meanwhile, students were recruited to academic committees — including the important planning, studies and curriculum committees — in which they played a real role in shaping the early university. Students were also chosen to be part of departmental meetings, sitting side by side with, and making decisions with, faculty members who were also their professors and mentors.

For their part, early faculty members were sometimes a little uncertain about the role they should or could play in founding the University. The earliest founders often had decided ideas, however, on what they wanted to see emerge in Lethbridge. The first dean of Arts & Science, Dr. Owen Holmes (DASc ’05), wanted a less authoritarian type of university than he had witnessed in his own educational lifetime. A product of the University of California, Berkeley, Holmes had already witnessed the earliest glimmerings of the liberal student revolt in the United States in the 1960s. He wanted to establish a culture of liberal education, and he sought to hire faculty members who were willing and pledged to do the work with him. He did not always promote a specific agenda but he always encouraged innovations brought forward by others — such as the establishment of Native American Studies, independent studies and colloquium studies — and he was open to an ever-evolving notion of what a liberal education might be.

Some early faculty members had gone through a gradual baptism in the mysteries of erecting a university as members of the College faculty. A few, like Holmes, had already served in other universities, and shared their enthusiasm for more experimentation and innovation. Other early faculty were fresh recruits, however, who had never heard of Lethbridge or the bold experiment being attempted here until they applied for a position and were hired. While the Faculty of Education had a hard core of veteran teachers and administrators, Arts & Science did not. There were few “gray eminences” to lead the way. When Dean Holmes spoke with every candidate for a faculty position in the Faculty of Arts & Science, he always made it clear that while teaching and research were duties that had to be pursued vigorously, community service was also expected. That service largely had to do with working to put one’s own department, faculty and university on a sound footing. If young faculty had not been so naive, we might have been intimidated.

Founders always like to believe that their era was glorious and positive. It is true that there was a genuine spirit of collegiality. When you are in a rowboat instead of an ocean liner, you need to row together and encourage one another. Yet, few were prepared for the heavy demands of democracy in the form of committees and planning, or for the very long meetings needed to establish new courses and procedures for university governance.

Two units of the new university faced special challenges to which both offered innovative solutions. The Faculty of Education, the only professional faculty of the early years, was thrust into immediate competition with well-established education Faculties elsewhere. Staffed with a few young professors and seasoned heavily with former principals and superintendents of public schools, the Education faculty revolutionized teacher training in Alberta, introducing more hands-on preparation through practicums and extensive student teaching. Within a decade, the word had reached the school districts: hire teachers trained at the U of L.

The fledgling fine arts departments, not yet occupants of their own building until the 1980s, improvised as well. Known for their somewhat bohemian beginnings at the old “Barn” at then Lethbridge Junior College — which partitioned classrooms for pottery from ones for sculpture or painting or drawing with makeshift curtains — the art department was relegated to the basement of the new physical education building in the 1970s. As it turned out, art and physical education became close, cooperative friends, each promoting the activities of the other. Music and drama scrambled too, pulling what resources and venues they could from other sources, in particular the non-university community. For all three fine arts departments, faculty and student engagement was intense and productive as they strived to improve the quality of the fine arts in the community while retaining their adventurous frontier spirit. The Fine Arts would eventually leave the Faculty of Arts & Science and continue to thrive. Yet there was the sense, throughout the first decade, that there were really three distinct units at the U of L: Arts & Science, Education and Fine Arts. The latter two pursued professional excellence in addition to the task of liberally educating all of our students.

A founder, and colleague of mine, once cynically contended that university faculty were not likely to hire new people who were better than themselves. Despite the fact that many faculty and administrators in the first generation were among the best persons we would ever employ, those hired after the first decade proved my colleague’s cynicism wrong time and again. All things considered, it might be argued that the best thing the first generation of the U of L did was hire the very best people possible, and then enlist them in furthering the liberal educational ideals of the U of L.

Story by James D. Tagg, PhD, Professor Emeritus.